"What is

essential in ballet is the dance, not the subject or story."

1

c/o Addison Wesley Longman

Jan. 11, 1998

Dear editor:

A worker at a poison control center answered a distraught mom

whose small girl had swallowed some ants. After reassuring her

there was nothing to worry about, the worker was about to hang up

when the mom added, "I fed her some ant poison." She was told to

bring the girl right in.

I believe the traditional interpretation of Theodore

Roethke— My Papa's Waltz, (in An

Introduction to Poetry) as "a somewhat comic

portrayal of a flawed but affectionate relationship," is much like

those ants: not exactly the brightest analysis, no more than ants

are high cuisine, but harmless to the student readers. Kim Larsen's

alternative analysis (in the ninth edition) however, is like that

ant poison, not the right place to address issues of child abuse,

and potentially damaging to the student mind.

A radio spot I hear is trying to encourage dads to spend some

time with their kids. It ends "It's easy to be a dad. All it takes

is time. And it takes a man to be a dad." I maintain that My

Papa's Waltz is one very good example of how easy it is to

be a dad, for a man to be a dad. The papa in the poem drinks a

man's drink, whiskey. He wears the pants in the family, whence the

belt buckle. He has a manly build so that when he romps vigorously,

the pans slide off the shelf. He may not have entirely succeeded in

making his mark on the world, but the world has left its marks on

him showing he tried. He is dominant over his woman at least to the

extent that she may not freely criticize him at will, which is not

to say she never finds a context for it. In short here is a man who

still finds essential time for his kid.

At least that is a very accessible interpretation of the poem

from a human perspective "...out West, where kids are still kids,

men are men, and women do the shopping."2

I believe it is a reach to project out from the dance to the

rest of the family behavior. Take an example of a prospective

mom:

At first she was quiet with the children, and they were

shy. But within a day they were friends. She brought her violin and

played for them. She fiddled Irish airs and Gypsy songs and danced

around the carpet as she played, head bobbing, auburn hair flying.

She laughed as she played. The children laughed too, and Lucy

clapped her hands. Then Sophie played a movement from a Bach

sonata. The children fell silent. After the Bach, Sophie stopped.3

It could just as easily be that Papa's waltz was the very ticket to

bring a shy man and boy into camaraderie. What about the whiskey on

his breath? Yes, but how far may we take such odors? I mean, as

when, "He leaned over and gave his father a strong hug—the

older man smelled comfortably of tweed and horses and old books,"4 do we

interpret that to mean his father goes to the races in his tweed

coat to bet on horses with his bookie? Then how can we be so sure

the other papa is drunk? Oh yes, it is the dark words the writer

selected. It happens every time. Here is a more clear cut example

of child abuse:

"Dennis shoved the boy behind him. The boy screamed and

wet himself."5

We can only infer the worst, even without the broader context:5

He looked at his watch: not yet midnight. The remains

of a log fire glowed in the living room fireplace, and the room was

still warm. He put on his toweled bathrobe and padded downstairs.

Shadows danced on the walls as he took a flashlight off the kitchen

counter. Hearing a soft footfall above him, he turned. Brian stood

on the staircase wearing his red flannel pajamas with pictures of

Mickey Mouse and Pluto.

"I heard something, Daddy."

"I think a cow's poking around in the

garbage. We threw out all those delicious chicken terriyaki bones

from supper, remember? Let's go look." With Brian at his

side, Dennis opened the kitchen door—the bitter cold night

air struck them a solid blow. He stepped outside, flicked on the

beam of the flashlight, and said, "Shoo!"

A black bear turned its great head towards him. It crouched on

all fours by the laden garbage cans. Its eyes, crimson buttons in

the yellow cone of the flashlight beam, suddenly and unaccountably

blazed with what struck Dennis as malevolence. Dennis smelled the

animal's meaty breath. It took a shuffling step towards them.

Dennis shoved the boy behind him. The boy screamed and wet

himself.

Gee, we were wrong to be so hasty to ascribe those dark words to

child abuse. We have some maybe dark words in the poem, but so

what?—we lack a broader context to define the family

relatings.

I believe there is a more productive approach. Your book is an

introduction to English literature, but this poem is about a dance,

so might we not try to find some well established precedent for a

parallel in an introduction to the history/art of dance?6

Rudolph von Laban (1879-1958), a native Hungarian,

founded the Central European dance school, in which ballet

technique was completely rejected and free body movements were

advocated. Mary Wigman (1886- ) and Kurt Jooss

(1901- ) were his most important disciples. Mary

Wigman's tremendous stage personality gripped her audiences for

many years; afterwards she became a teacher. She was the

outstanding figure of German expressionism in the art of the dance,

a movement that was (in Germany and Holland during the twenties and

thirties) and is (in the United States today—e.g., Martha

Graham) almost entirely practiced by women. These are dancers who

"express themselves," believing that they can translate their

deepest feelings into "dance."

Kurt Jooss was primarily a theater artist who addressed the

world with an ideological message. The Green Table

will always remain the masterpiece of the dance of those years.

This dance drama had its première in Paris on July 3, 1932,

in a competition at the International Congress of the Dance, and

won the first prize, deservedly. By 1947 it had already had over

3,200 performances. The Green Table had an

unmistakable influence in the world of dance, particularly on

British ballet, although it does not belong to the realm of ballet

on pointes. In later years Kurt Jooss came to the conviction that

no school and no dance system can be built on the basis of Laban's

ideas, nor on any other fixed system, for that matter.

If we draw a parallel between Papa's waltz and German

expressionism, then Mrs. Larsen's "chaos" is Laban's "free

body movements," the "domineering" papa is only "Mary Wigman's

tremendous stage personality [that] gripped her audience," and the

frowning housewife is merely the uncomprehending males facing

"These women dancers who 'express themselves,' believing that they

can translate their deepest feelings into 'dance.'" In other words,

just as Wigman's dance art was a girl thing, Papa's waltz was a guy

thing, and the parallel drawn helps the other sex comprehend it.

Furthermore, Jooss' "unmistakable influence in the world of

dance" translates into the unmistakable influence a father has on

his boy's development, which is why he needs to spend (quality?)

time with him. A very interesting point is the last one where Jooss

rejects any fixed system of dance. It hints that a boy's

development needs to have some random factors influencing it in

order for him to develop into a fully functioning

adult—shades of chaos theory for math and science majors to

relate to. Mind you, this parallel example is from established

dance history, not idle speculation.

From here we may wish to speculate on a fleshed-out family life,

but we would only be betraying our own feelings as the poet left

that area to our imagination. There is one way to avoid that

pitfall in an introductory literature course, and that is to find

some parallel context in literature (fiction) to dovetail with

papa's waltz. That way we are still studying literature.

SOPHIE THREW HER arms around him as she had not done in

months. "Thank you," she said. He felt

that all her heart went into those two simple words. But he was a

little drunk, unable to stop his tongue from voicing what was on

his mind.

"You're welcome. All in a day's work. I may have

lost a friend or two and I had to pillory a deputy district

attorney, but the son of a bitch probably deserved it. Never mind

that he was right and I was in the wrong. I just keep wondering why

I have this sour taste in my mouth. Is it the bourbon? Must

be."

"Don't act like this, Dennis, please. Whatever

you had to do, you did the right thing."

"Did I?" Dennis said. "Convince me. Tell all."

The telephone rang. Sophie answered, and Dennis bounded up the

stairs two at a time to hug his children. "Ouch, Daddy," Lucy said. "Too

hard."

He flung off his suit, shirt, and tie, all his clothes, then

plunged into the shower. In the frosted glass stall he shut his

eyes and stood under the drumming beat of the hot water for ten

minutes, as if soap and steam could wipe off the grime of the

trial. When he finally came out to towel down, Sophie was waiting

for him.

"That was my father who called. They wanted

us to come over for dinner, to celebrate." It sounded so

domestic, as if he had won a promotion or it was someone's

birthday. "But I said no." Sophie

wasn't smiling; she looked oddly flushed. "I

need to talk to you, Dennis. I'm sorry about how you feel but I

think after I've talked to you, you may feel differently. I want to

explain Springhill. It can't wait. It has to be tonight. I have so

much to tell you—all that I couldn't tell you

before."

He was bewildered by her urgency, but not unhappy at the thought

that he wouldn't have to spend the evening feasting with Scott and

Bibsy. He had seen more than enough of them last week. He'd done

what had to be done, but he wondered if he would ever feel the same

warmth toward his in-laws as he had before he came to the

conclusion they were guilty as charged. He had defended them with

full vigor: that was his obligation as a lawyer, and he had won. It

wasn't his obligation to forgive and forget.

The buzz of the alcohol began to wear off. "I

want to spend some time now with the kids," he said.

"I understand. Do it, of course. I meant after

dinner."

Sophie had barbecued two chickens and baked a peach pie. Later,

at the computer, Dennis worked with Brian and Lucy on a new astronomy

program. He showed them the planetal orbits.

The moon whizzed around the earth; the earth flew around the sun.

It was all orderly and yet it made no sense.7 Just like life,

he thought. By the time the children were bored and ready for bed

Dennis felt that life was beginning to move back to normalcy. The

old fundamental truth struck home: whatever happens, life goes on.

The planets move on their tracks and so do we.8

Comparing Sophie's Tale with Papa's Waltz, both papa and the lawyer

got dirty at work, only papa's "hard caked dirt" was cleaner than

the lawyer's "grime of the trial." Nevertheless, although the

lawyer did his job well, he placed his family (in-laws) above his

law school idealism. His mind got disjointed by the work he did on

behalf of his family. If papa were anything like him, his battered

knuckle was got leaning over backward for his family. Although the

lawyer had friends outside the family, he placed his family above

them. He was a veritable knight in shining armor. He made up for

his absence from his family by seeking time with his kids before

their bedtime. His wife's talk had to wait until after. With his

children he was exuberant to a fault. The white collar worker drank

bourbon and papa whiskey. Sophie's countenance—"wasn't

smiling"—had to do with her forced patience before she got a

chance to confess. Papa's wife's frown could be because she must

hold back a little longer from confessing to her saint of a

husband, at least as much as any other reason which their kid

probably wouldn't even be aware of.

The difference between papa and the white collar worker is the

former whirled bodies while the latter whirled planets on the

computer. If we put papa into modern terms of a dad being a klutz

on a new computer, we would probably not jump to the conclusion he

was drunk, even though he had a few drinks to alleviate pressures

at work. What papa's waltz has in common with the computerized

planets and even life itself is, "It was all orderly and yet it

made no sense."

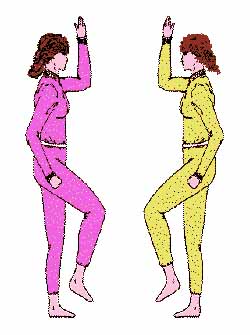

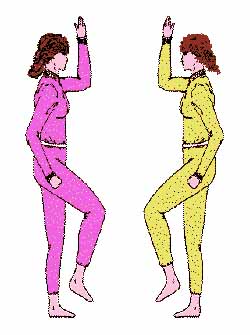

As a dance, however, papa's waltz is an advanced version of the

Cross-Crawl (enclosed) integrating a

child's development, smell from above (whiskey), touch on right

(ear), sight on left (mom's frown), and taste beneath (fresh bed

sheets). Sound was the music, papa's tapping, and his missed beats

and the falling pans integrate human errors and random factors into

the learning.

Cross-Crawl (enclosed) integrating a

child's development, smell from above (whiskey), touch on right

(ear), sight on left (mom's frown), and taste beneath (fresh bed

sheets). Sound was the music, papa's tapping, and his missed beats

and the falling pans integrate human errors and random factors into

the learning.

Sincerely Yours,

Earl Gosnell

Poet Laureate of Longfellow, Colorado

2 encl.

[TOP]

Home

Introduction

Letter 2 —

examines archetypes in the poem and explains the poem's

meaning.

Letter 3 — contrasts

the poem with child abuse literature.

NOTES

1. Hans Verwer, Guide to

the Ballet (US: Barnes & Noble #282, 1963)

Preface, v. Back to document

2. Clifford Irving, The

Spring (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996) p. 22. Back to document

3. Ibid., p. 39. Back

to document

4. Ibid., p. 42. Back

to document

5. Ibid., p. 56. Back

to document

6. Verwer, p. 109. Back to document

7. Isn't that the lesson in Job in

the Bible—where Job's wife actually voices her opinion? Back to document

8. Irving, pp. 205-6. Back to document

View My Guestbook

Sign My Guestbook

Author:

Earl Gosnell

1950 Franklin Bv., Box 15

Eugene, OR 97403

Contact:

feedback bibles.n7nz.org

bibles.n7nz.org

Copyright © 1998, Earl S. Gosnell III

This work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Licence.

Permission is hereby granted to use the portions original to

this paper--with credit given, of course--in intellectually honest

non-profit educational material. The material I myself have quoted

has its own copyright in most cases, which I cannot speak for but

have used here under the fair use doctrine.

I have used material from a number of sources for teaching,

comment and illustration in this nonprofit teaching endeavor. The

sources are included at the end in notes. Such uses must be judged

on individual merit, of course, so I cannot say how other uses of

the same material might fare.

Any particular questions or requests for permissions may be

addressed to me, the author.

Web page problems?

Contact:

webfootster32 bibles.n7nz.org

bibles.n7nz.org

Cross-Crawl (enclosed) integrating a

child's development, smell from above (whiskey), touch on right

(ear), sight on left (mom's frown), and taste beneath (fresh bed

sheets). Sound was the music, papa's tapping, and his missed beats

and the falling pans integrate human errors and random factors into

the learning.

Cross-Crawl (enclosed) integrating a

child's development, smell from above (whiskey), touch on right

(ear), sight on left (mom's frown), and taste beneath (fresh bed

sheets). Sound was the music, papa's tapping, and his missed beats

and the falling pans integrate human errors and random factors into

the learning.